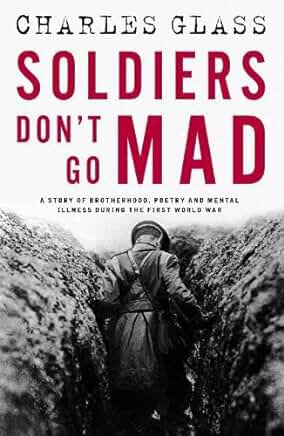

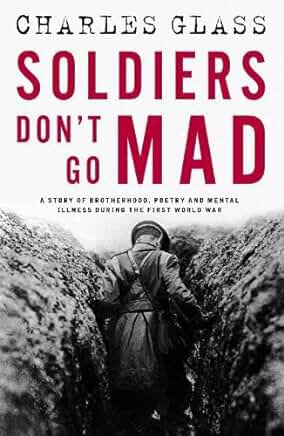

Published to critical acclaim in the US, Soldier’s Don’t Go Mad will be published in the UK in November 2023

A poignant history of the friendship between two Great War poets alongside a narrative investigation of the origins of PTSD and Literary response to World War I

Book blurb

Second Lieutenant Wilfred Owen was twenty-four years old when he was admitted to the newly established Craiglockhart War Hospital for treatment of shell shock. A nascent poet, trying to make sense of the terror he had witnessed, he read a collection of poems from a fellow officer, Siegfried Sassoon, and was impressed by his portrayal of the soldier’s plight. One month later, Sassoon himself arrived at Craiglockhart, having refused to return to the front after being wounded during battle.

Over their months at Craiglockhart, each encouraged the other in their work, their personal reckonings with the morality of war, and their treatment. Therapy provided Owen, Sassoon, and their wardmates with insights that allowed them to express themselves better, and for the 28 months that Craiglockhart was in operation, it notably incubated the era’s most significant developments in both psychiatry and poetry.

Soldiers Don’t Go Mad tells for the first time the story of the soldiers and doctors who struggled with the effects of industrial warfare on the psyche. As he investigates the roots of what we now know as PTSD, Glass brings historical bearing to how we must consider war’s ravaging effects on mental health, and the ways in which creative work helps us come to terms with even the darkest of times.

The outbreak of war across across Europe in 1914, ushered in a new and unprecedented era of modern warfare. Soldiers faced relentless machine-gun fire, incredible artillery power, flame-throwers, and gas attacks. Within the first four months of the First World War, the British Army recorded the nervous collapse of ten percent of its officers.

During the war, Craiglockhart Hospital treated around 1800 officers with shell-shock. And it was here that two of the world’s greatest war poets met — Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Despite differences in age, class, education, and interests, both were outsiders – soldiers unfit to fight, gay men in a homophobic country, and Britons unwilling to support the war. But more than anything else, they shared a love of the English language and poetry. As their friendship evolved over their months as patients at Craiglockhart, each encouraged the other in their work, in their personal reckonings with the morality of war, as well as in their treatment. The friendship acted as doctor, nursing them to both health and creative achievement.

Drawing on rich source materials, as well as Glass’s own deep understanding of trauma and war, Soldiers Don’t Go Mad tells for the first time the story of the soldiers and doctors who struggled with the effects of industrial warfare on the human psyche. Writing beyond the battle- fields, to the psychiatric couch of Craiglockhart but also the literary salons, halls of power, and country houses, Glass charts the experiences of Owen and Sassoon, and of their fellow soldier-poets, alongside the greater literary response to modern warfare.

Written in the midst of the pandemic, when Charles Glass was hospitalised with Covid-19, Soldier’s Don’t Go Mad provided his own literary solace. Gripping, thorough and informative, Soldier’s Don’t Go Mad is this winter’s essential read.

‘Thoroughly researched and lucidly written, this is an immersive look at the healing power of art and a forceful indictment of the inhumanity of war’

Publisher’s Weekly

“What Mr. Sassoon has felt to be the most sordid and horrible experiences in the world he makes us feel to be so in a measure which no other poet of the war has achieved.”

Virginia Woolf, The Times Literary Supplement

My thoughts

On the 11th November each year we remember the those who have fought and died in battles and wars particularly those who fought with the allies (British, Commonwealth, American some European countries) but more and more it is becoming not just a remembrance of them but also of the enemy countries whose individual lives were lost. The 11th November is the date that the First World War (WWI) – the Great War, the War to end all wars – was finally ended and an armistice was declared.

Soldier’s Don’t Go Mad by Charles Glass is a very poignant reminder of why we should continue to remember the fallen, those who fought and died, but also those who fought and returned particularly those who returned broken either physically, disabled from their injuries, or mentally, disabled from what they saw, what they lived through but no longer could reconcile in their minds.

It is this latter group of men and specifically the officers of WWI who passed through Craiglockhart War Hospital that Charles Glass has taken to demonstrate the effects of war on the minds of those who fought and how through the work at this facility by its doctors brought about a greater understanding and better treatment of these men.

Where are the men, the ordinary soldiers, sailors and airmen in this? Well we are in no doubt from this book that they were treated in a completely different manner if indeed they were treated at all it was very badly and sent back to the front, put in a lunatic asylum or taken as cowards and shot. This also happened to some officers but they, at least, had a chance of being sent to hospitals with better facilities and doctors who had some understanding of what was generally termed as ‘shell shock’ and a shining example was Craiglockhart situated near Edinburgh.

The book opens with a series of statistics showing the number of men and these were young men we must remember who died in battle – cannon fodder – who died in the battles of WWI – Ypres, the Somme and more. We move on to vignettes of what took place, the stories of what a number of men who were treated at Craiglockhart went through which brought them back to be treated there. They are – the numbers and the stories – harrowing to read but this is an important record, a reminder, to those of us who were not there of what went on.

It is no surprise on reading this that there would be those who would object to returning to such horror, that there were those who could not contemplate fighting at all (conscientious objectors were given non-combatant work or worse).

Then we read that two, indeed more than two, poets were treated at Craiglockhart but most importantly – Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. Sassoon was older and a more established poet who was from a well to do background; Owen younger, an emerging poet and from a more modest background. Yet they became friends. Sassoon saw the potential in Owen but by the time they both had left Craiglockhart has bonded over their mutual love of poetry. Their friendship and poetry was as much a part of their treatment as their sessions with their doctors who actively supported these alongside physical therapy and recounting their dreams, feelings and experiences from battle and the past.

They had ended up in Craiglockhart from different directions. Sassoon was refusing to return to a war that he believed was being manipulated by politicians and others for political or economic gain. Because of his connections and background the Military preferred to consider him unfit for duty due to a breakdown than subject themselves to a court martial against Sassoon that would have been at least embarrassing and potentially worse with regard to showing the general public what was actually happening.

Owen on the other hand was sent there entirely due to injury and the telltale signs of shell shock from his experience in the trenches and fields of battle.

Craiglockhart had the best performance of all the similar facilities in the U.K. with just under 50% as compared to facilities that still used treatments such as electric shock therapy whose performance was, it seems, under 10%.

We must not forget that even these forward thinking and cutting edge treatments were still being used in order to get these men back to the battlefield (not forgetting the sea and air). To fix them in order to return them to the very conditions that brought them back in the first place!

Sassoon returned to the front for a while after serving in Ireland and Egypt he was strangely eager to return to battle but was unable to carry on and after being diagnosed with fatigue was sent to Craiglockhart were he was assigned to Lennel, a house in Scotland used as part of the Craiglockhart War Hospital, to rest.

Owen was also sent back to the front were he fought valiantly to the end. In a letter replying to Siegfried Sassoon who was convalescing at Lennel Owen wrote:

“While you were apparently given over to wrens, I have found brave companionship in a poppy, behind whose stalk I took cover from five machine guns and several howitzers.”

Wilfred Owen, 10 October 1918

Both these men had received the Military Cross during the war.

Soldiers Don’t Go Mad by Charles Glass is an important and impactful book which I found to be well worth reading. The information is well researched and brings together through statistical information, the telling of real life experiences and the determination of the doctors and patients at Craiglockhart what the treatment of those with shell shock could and should be even when the establishment had very little time for it they demonstrated that they were capable of treating, often completely, the mental illnesses brought on from being exposed to the conditions of battle. That improvement in the treatment, conditions and understanding of PTSD as we now call it and in mental health generally for the armed services and beyond is a testament to Craiglockhart and its doctors.

This book was a sobering yet fascinating and compelling. I hope that it will be a book that students and readers will use to learn and understand about poetry and how it can be used to help people work through their experiences in trauma; the leaps and bounds that mental health treatment and understanding has come on in the last hundred years or so, although there is still more needed. It is a book that should be used as a tool to teach about mental health issues, about how we should always give support to men (and women) in the services indeed everyone, everywhere suffering from mental illness. Not forgetting about the importance of poetry (of art and writing, too) and of friendship which often gives us the greatest support.

This is a very readable book and one that the author has written in very difficult circumstances that I would highly recommend reading.

Thanks

Many thanks to Grace for the invite to join this fascinating BlogTour and to the publisher Bedford Square for an eCopy of Soldiers Don’t Go Mad by Charles Glass.

‘A lucid, comprehensive and highly engaging account of a watershed in British medical and literary history’

Sebastian Faulks, author of Birdsong, Charlotte Gray, and Snow Country

BlogTour

Watch out for the BlogTour of Soldiers Don’t Go Mad by Charles Glass across social media during November and enjoy reading the thoughts of some wonderful bloggers. There are links below to acquire your own copy of this truly interesting book.

In the meantime why not visit some of these terrific blogs to read more about Soldiers Don’t Go Mad –

Information

Published: bedfordsquarepublishers (23 November 2023)

Hardback |RRP: £22.00 |ISBN: 9781835010150 |Extent: 352 pages

Paperback |RRP: £12.99 |ISBN: 9781835010174 |Extent: 352 pages

Ebook | RRP: £9.99 | ISBN: 9781835010167

Buy: AmazonSmileUK | Hive | Bookshop.org (affiliate link) | Your local bookshop | Your local library | BedfordSquarePublishers

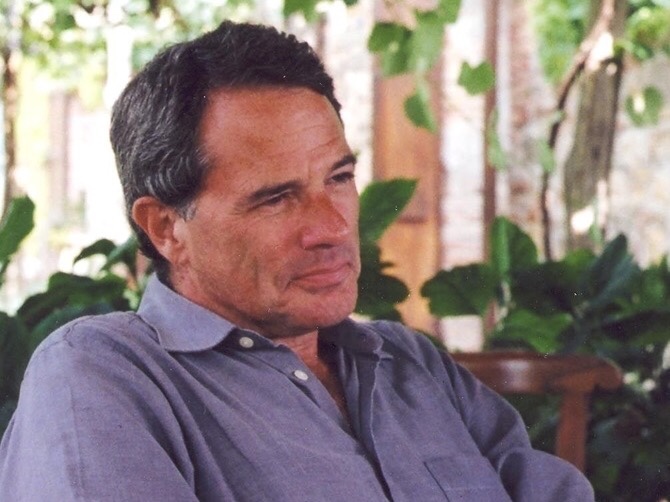

Charles Glass is an American-British award-winning journalist, author, broadcaster and publisher. He was ABC News chief Middle East correspondent from 1983 to 1993, and has worked as a corre- spondent for Newsweek and The Observer. He divides his time among the south of France, Tuscany, London, and the Middle East.

ALSO BY CHARLES GLASS

They Fought Alone | The American Hospital of Paris during the Two World Wars | Syria Burning | Deserter | Tribes with Flags | Americans in Paris | The Northern Front | The Tribes Triumphant | Money for Old Rope

One response to “Soldiers Don’t Go Mad: A Story of Brotherhood, Poetry and Mental Ill- ness During the First World War by Charles Glass #ComingSoon #Friendship #WWI @bedsqpublishers #SoldiersDontGoMad”

[…] Soldiers Don’t Go Mad by Charles Glass for a BlogTour from Grace Pilkington Publicity and Bedford Square Publishers (23 Nov. 2023) my spot was 30th November. […]

LikeLike